1776 the Musical

Through all the gloom, Through all the gloom, I can see the rays of ravishing light, And glory!

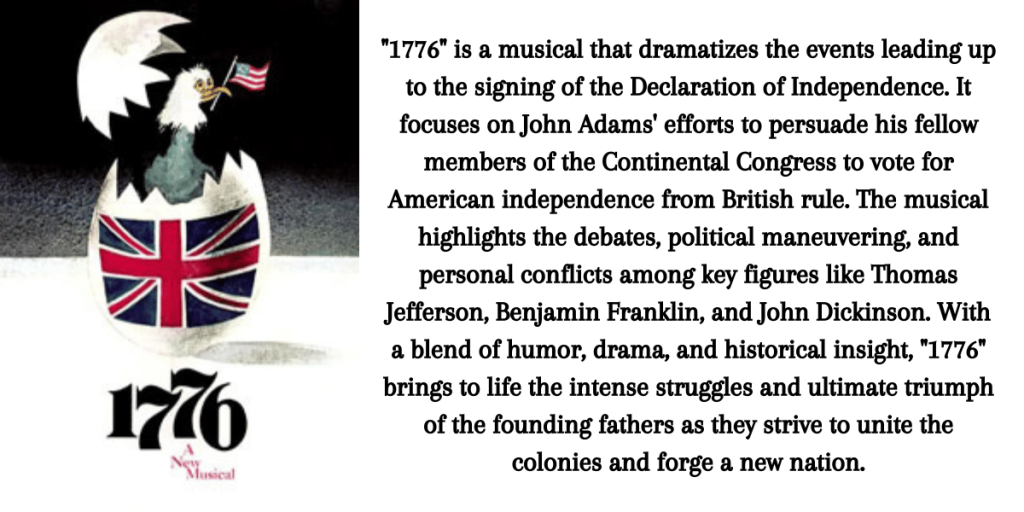

“1776,” the acclaimed musical that brings the founding of the United States to vibrant life, captures the riveting drama and heated debates that defined the creation of the Declaration of Independence.

With its debut on Broadway in 1969, this Tony Award-winning production, composed by Sherman Edwards and scripted by Peter Stone, offers a compelling blend of history, humor, and humanity. Set against the backdrop of the Continental Congress, “1776” illuminates the challenges, compromises, and convictions of the American Revolution’s key figures, drawing audiences into the exhilarating and often contentious journey toward independence.

- 1776 the Musical

- The Basics of “1776”

- The History Behind “1776”

- The Plot of “1776 the Musical”

- The Characters of “1776 the Musical”

- Exploring the Music, Lyrics, and Dance of “1776 the Musical”

- Reality Vs. Fictional: “1776 the Musical” Historical Inaccuracies

- Broadway Buzz: 1776

- Conclusion

- Sources

- “1776 the Musical” FAQ

- About the Author

The Basics of “1776”

Book by Peter Stone

Music and Lyrics by Sherman Edwards

Time/Date: Summer of 1776

Place: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Genre:

- Period/Historical/Biographical

- Drama

- Comedy

Target Audience: PG

Duration: 1 Hour and 45 Minutes

Performance Groups:

- High School Theatre

- College Theatre

- Community Theatre

- Professional Theatre

The History Behind “1776”

1776: A Year of Revolution and Change

1776 was a pivotal year in world history, particularly marked by significant events in the American colonies. The most notable event was the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. This document, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson, proclaimed the thirteen American colonies’ independence from British rule and laid the foundation for the creation of the United States of America.

The year also saw crucial battles in the American Revolutionary War. The Battle of Long Island in August resulted in a significant defeat for the Continental Army under General George Washington, leading to the British capture of New York City. Despite setbacks, Washington’s strategic brilliance shone through with the daring crossing of the Delaware River on December 25-26, leading to a surprise attack and victory at the Battle of Trenton.

Thus, 1776 was a year marked by revolutionary ideas and battles, significantly altering the course of history and laying the foundation for modern democratic governance and economic thought.

The Writing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776

The Declaration of Independence, one of the most important documents in American history, was drafted in the midst of the American Revolutionary War. The process began in earnest in June 1776 when the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. Tensions with Britain had been escalating, and the desire for complete independence from British rule was becoming a consensus among the colonies.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a resolution declaring that the colonies “are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” This resolution led to heated debates within Congress, resulting in the formation of a committee to draft a formal declaration. The committee consisted of five members: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston.

Thomas Jefferson, known for his eloquent writing style, was tasked with drafting the document. He worked in seclusion in his rented rooms at the Graff House in Philadelphia, drawing upon existing documents such as the Virginia Declaration of Rights and incorporating Enlightenment ideals. His draft emphasized natural rights, the social contract, and the colonies’ grievances against King George III.

The committee reviewed and made minor edits to Jefferson’s draft before presenting it to Congress on June 28. Over the next few days, Congress debated and revised the document. Some sections were removed or altered to ensure broader support, including a passage condemning the slave trade, which was contentious among delegates.

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted in favor of Lee’s resolution for independence. Two days later, on July 4, Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence. John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, famously signed the document first, followed by other members.

The Declaration was publicly read in Philadelphia on July 8, and copies were distributed throughout the colonies and to the Continental Army. It served as a powerful statement of the colonies’ intentions and a rallying cry for those fighting for independence.

Thus, the drafting and adoption of the Declaration of Independence were pivotal moments in 1776, encapsulating the American colonies’ desire for self-determination and setting the stage for the birth of a new nation.

The Creation of “1776 the Musical”

“1776” (1969 Musical)

A passion project turned Tony Award winning musical, this historic show would not have happened without Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone.

A history teacher full time and a composer and lyricist on the side, Edwards had a vision to create a musical surrounding the events about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He was so inspired that he ended up leaving his jobs and writing the first draft of the book, music and lyrics of the musical after 9 years of research, writing, and repeating.

“I wanted to show [the founding fathers] at their outermost limits. These men were the cream of their colonies. … They disagreed and fought with each other. But they understood commitment, and though they fought, they fought affirmatively.”

Gaining inspiration wasn’t hard, but finding collaborators who supported and shared his vision was incredibly difficult. Many kicked him out of the audition room believing his story was dumb and clashed with the cultural events that were happening during that time. The political climate was intense with the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, and the anti-war movement happening all across America.

The only person who saw what Edwards was envisioning was producer Stuart Ostrow. He saw promise in Edwards’ story and how it could connect with the American people with its rebellious spirit, questioning authority, breaking the status quo, and challenging opposition. However, Ostrow knew the story needed some tweaking so he called in Peter Stone, a successful writer in the Hollywood space.

Interestingly, a few years before, Edwards did ask help from Stone, but Stone passed up on the offer. However, when Stone was approached again and he heard Edwards music, he loved the idea. This wasn’t going to be another history lesson, but a true musical about real men fighting a real war doing something no one in history has ever done before.

During the rewriting process, Stone decided to focus on the arguments that happened occurred during that year such as the issue of slavery and the topic of what true independence really means. Of course, he also took historical liberties with the story: the calendar and the tally board were never in the Independence Hall, the signing of the Declaration of Independence was not signed on July 4 by 56 men, Thomas Jefferson did return to Virginia to visit his wife, Samuel Adams was John Adams’s cousin, and much more.

Fun Fact

People have told Stone that “1776” should have been a conventional play due to its heavy dialogue and historical content. However, he felt the songs added a playful tone that brought the historical characters to life.

Despite the changes, Stone made sure the main themes he and Edwards wanted to express were consistent throughout the entire story. They decided that John Adams would be the central character and his main objective throughout the story was to persuade all 13 colonies to vote independence which also becomes the main conflict of the show. Almost every scene was confided inside the Independence Hall to further the themes in the story. All changes that were made were only to enhance the drama even though the audience knew the outcome. Once Stone was finished with rewriting the story, it was deemed an unconventional musical as there were no dancing women (which was common at the time), no intermission (during the 1969 run), and had the longest running time with no music being over 30 minutes.

Fun Fact

Scene Three of “1776” holds the record for the longest time in a musical without any music: over thirty minutes elapse between “The Lees of Old Virginia” and the next song, “But Mr. Adams.” In a DVD commentary, writer Peter Stone mentions that he tried adding songs during this part, but none felt right. For the first time in history, musicians were allowed to leave the orchestra pit during this scene.

Despite this, Edwards, Stone, and Ostrow found director Peter Hunt and began production. After many changes, conflicts, and tryouts in New Haven, Connecticut, and Washington D.C., the show finally opened on Broadway on March 16, 1969. The show ran for 1,217 performances and had a successful national tour for 2 years winning numerous awards along the way. The story that was rejected over and over became a national, historical success.

“1776” (1972 Film)

After the show became a smash hit on Broadway from both audiences and critics, Hollywood producer Jack L. Warner bought the film rights to the musical for $1.25 million in November 1970.“The first time I saw the play on Broadway, I visualized the chance to show millions of people the spirit in which this country was founded. I didn’t do the thing because it would make money. I figured what the country needed was an idea of where it came from and how we go the freedom we all enjoy.”

“The first time I saw the play on Broadway, I visualized the chance to show millions of people the spirit in which this country was founded. I didn’t do the thing because it would make money. I figured what the country needed was an idea of where it came from and how we go the freedom we all enjoy.”

With Columbia Pictures teaming up with Warner, he brought in the majority of the original cast, crew, and creative team that created the musical. Filming went smoothly especially since the cast knew their lines and songs, and the crew and creative team knew the story.

However, when post-production was completed, a special screening was shown to the U.S. President at the time, Richard Nixon. Nixon, reportedly, enjoyed the film but he and his staff asked the musical number “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” be cut. Warner agreed and believed he had all the cut negative destroyed. So, when the film officially premiered on November 9, 1972, the scenes and song was not there. Finding this out, Hunt and a team of specialists sent a nine month period inspecting over 550 cans of negative and audio outtakes to see if the original material still existed. Thankfully, they found the original material, and Hunt oversaw the restored edit of the picture. Soon, he created the director’s cut of “1776”.

The film was a massive hit in Radio City Music Hall when it premiered but flopped in movie theaters worldview.

“1776” (1997 Musical Revival)

Many years later, Roundabout Theatre Company revived the show opening on August 4, 1997. The production was very successful that it had a commercial run. In total, it ran for 333 performances and 34 previews.

“1776” (2022 Musical Revival)

Another revival of “1776 the Musical” was underway under the direction of Diane Paulus, but plans were delayed when 2020 happened.

As a result, everything was done through Zoom, and Jeffrey L. Page was brought to direct the musical alongside Paulus. It was soon announced that the revival cast was actors who were female, non-binary, and trans with no males in sight.

The revival had a three month show in 2022 on Broadway in Roundabout Theatre before beginning a 16-city national tour in 2023. Unfortunately, unlike the previous shows, this revival did poorly with negative reviews.

The Plot of “1776 the Musical”

Act I

On May 8, 1776, as the Second Continental Congress gathers in Philadelphia at what is now Independence Hall, tension simmers beneath the surface. John Adams, the contentious delegate from Massachusetts, seethes with frustration as his calls for debate on independence go unheard. The sweltering heat only heightens the discontent among the delegates, who urge Adams to (“Sit Down, John”). In response, Adams criticizes the Congress for its inertia, dismissing its efforts with disdainful remarks like (“Piddle, Twiddle, and Resolve”). He then reads a heartfelt letter from his wife Abigail Adams, who, in his mind, offers him solace (“Till Then”). Amid this turmoil, Adams encounters Benjamin Franklin, who advises him to let another delegate, more favored by his peers, introduce the resolution for independence. Franklin then arranges for Richard Henry Lee of Virginia to present the case to the Virginia House of Burgesses, nudging Lee to champion the pro-independence resolution (“The Lees of Old Virginia”).

Weeks later, Dr. Lyman Hall of Georgia joins the Second Continental Congress, meeting key figures like Andrew McNair, the custodian; Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island; Edward Rutledge of South Carolina; and Caesar Rodney of Delaware. As Congress convenes, John Hancock, the president, notes the continued absence of the entire New Jersey delegation. A somber report from George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, is read aloud by Charles Thomson, the Congressional Secretary. The session is briefly disrupted when a fire wagon rolls by, providing a moment of levity. Shortly after, Lee arrives with a resolution for independence. With renewed energy, Adams eagerly seconds the motion to begin debate on the resolution.

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, a conservative and staunch royalist, swiftly proposes to table the debate on independence. The vote is narrowly in favor of continuing the discussion, which only fuels Dickinson’s assertion that the push for independence is an overreaction to minor disputes with Great Britain. As the debate grows increasingly intense and personal, it erupts into a physical altercation between Dickinson and Adams, and Rodney, already weakened by cancer, collapses. Rodney is transported back to Delaware, leaving George Read as the sole remaining delegate from their delegation. With Read’s conservative stance, Rutledge pushes to swiftly end the debate and vote on independence, anticipating a likely defeat. At this critical juncture, the new New Jersey delegation arrives, with Reverend John Witherspoon announcing he has explicit orders to vote for independence. Sensing a chance for success, Adams urges for an immediate vote, confident that Hancock, who presides over the Congress and is a staunch advocate for independence, will cast the deciding vote.

Out of nowhere, Dickinson proposes a new motion: that any vote in favor of independence must be unanimous. The vote predictably ends in a tie, but Hancock surprises everyone by casting his vote for unanimity. He argues that without a unified stance, loyalist colonies might turn against those supporting independence, potentially igniting a civil war among the colonies.

In a bid to salvage the independence movement, Adams proposes postponing the vote to allow time for drafting a formal Declaration of Independence. This declaration could sway European courts and rally support for the American cause, while also giving Adams a chance to win over the anti-independence delegates. The vote ends in another tie, but Hancock sides with Adams, as many delegates are eager for a break. Before adjourning, Hancock appoints a committee to draft the declaration, consisting of Adams, Franklin, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert Livingston of New York, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Despite Jefferson’s imminent departure to visit his wife, whom he hasn’t seen in six months, the committee debates who should write the declaration (“But, Mr. Adams”). Adams is deemed dislikable, Franklin is reluctant to engage in political writing, Sherman lacks writing skills, and Livingston is preparing to celebrate the birth of his new son. The task ultimately falls to a hesitant Jefferson.

A week later, Adams and Franklin visit Jefferson, who has been brooding over his predicament. Unbeknownst to Jefferson, Adams has arranged for his beloved wife, Martha Jefferson, to visit, believing that resolving Jefferson’s personal issues will also help their cause. Martha arrives, and Adams and Franklin leave the couple to enjoy their reunion. Alone, Adams exchanges more letters with his wife Abigail (“Yours, Yours, Yours”). The following morning, Adams and Franklin return to formally meet Martha, curious about how the reserved and introspective Jefferson won her heart (“He Plays the Violin”). When Jefferson arrives, he quietly takes his wife’s side and, through a note, requests that Adams and Franklin to go away.

In June, as Congress appears mired in stagnation, a troubling report from Washington spurs Adams to challenge Samuel Chase of Maryland to accompany him and Franklin to the Army camp in New Brunswick, New Jersey, to assess the dire conditions. With the departure of the liberal delegates, only the conservatives remain in the chamber. John Dickinson leads his fellow conservatives in defending their wealth, status, and political stance (“Cool, Cool Considerate Men”). As they leave, only Andrew McNair, the custodian, the Courier, and a Workman are left behind. The courier then recounts the tragic story of how his two closest friends were killed on the same day at Lexington (“Momma Look Sharp”).

Act II

A few days later, Jefferson stands outside the chamber as Thomson reads the declaration to Congress. Adams and Franklin arrive, jubilant: a demonstration by the Continental Army has swayed Chase, and Maryland will now vote in favor of independence. They praise Jefferson for his efforts, and Franklin likens the birth of the new nation to the hatching of a bird. The group debates which bird would best symbolize America: Franklin advocates for the turkey, Jefferson proposes the dove, but Adams firmly supports the eagle. The others reluctantly accept Adams’s choice (“The Egg”).

On June 28, Hancock inquires whether there are any proposed changes to the Declaration of Independence. Numerous delegates suggest revisions, but Rutledge strongly objects to a clause condemning the slave trade. He accuses the northern colonies of hypocrisy, pointing out their own benefits from slavery through the Triangle Trade (“Molasses to Rum”). Rutledge leads a walkout with delegates from both Carolinas and Georgia, causing the resolve of the remaining delegates to waver, and many follow suit. Adams’s confidence falters after a heated disagreement with Franklin, who argues they cannot sway the others to abolish slavery. In a moment of doubt, Adams mentally seeks guidance from Abigail, who reminds him of his dedication to the cause. Reinvigorated by her support and the arrival of promised kegs of saltpeter, Adams regains his resolve. He sends Franklin to persuade Pennsylvania’s James Wilson and asks Jefferson to speak with Rutledge. Alone, Adams re-reads a dispatch from Washington and wonders (“Is Anybody There?”). Dr. Hall, hearing Adams’ question, answers by changing Georgia’s vote on the tally board from “Nay” to “Yea.”

On July 2, Hancock calls for a vote on the Lee Resolution. At this critical moment, Rodney and Thomas McKean return to Congress, ensuring that Delaware will support independence. Thomson calls on each delegation, and while Pennsylvania passes on its first call, the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies all vote in favor, with New York abstaining. When South Carolina is called, Rutledge demands the removal of the slavery clause in return for his colony’s support. Franklin counters that achieving independence is the first step before addressing slavery, and Jefferson agrees to strike out the contentious passage. North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia all vote “yea.”

On Pennsylvania’s second call, Dickinson is about to cast a “nay” vote when Franklin requests a poll of the delegation. Franklin votes “yea,” and Dickinson votes “nay,” leaving the decisive vote to Wilson. Previously aligned with Dickinson, Wilson now fears that siding with him might label him as the man who thwarted American independence. In a pivotal moment, he changes his vote to “yea.” With twelve colonies voting in favor, none against, and one abstaining, the resolution is unanimously adopted.

Hancock proposes that no delegate be permitted to remain in Congress without signing the Declaration. Dickinson states that he cannot, in good conscience, sign it as he still hopes for reconciliation with England. However, he commits to joining the army to support and defend the new nation. As Dickinson exits the chamber, Adams leads Congress in a salute to his decision.

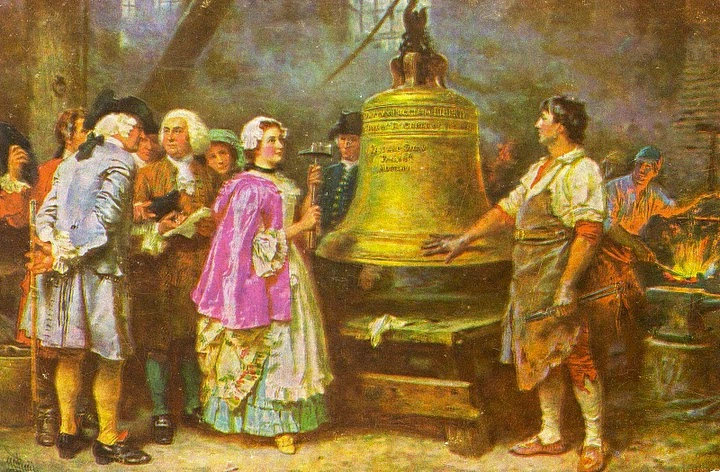

On July 4, as McNair rings the Liberty Bell in the background, Thomson calls each delegate to sign the Declaration. The delegates stand frozen in place as the bell rings with increasing intensity.

The Characters of “1776 the Musical”

Main Characters

John Adams – The Massachusetts delegate. A Harvard graduate and experienced lawyer. A leading voice for separation from England and a strong stance for Independence in America. He is known for his strong oratory skills, a brilliant mind, being short, but has a bold and brash personality with a slight Boston dialect. Unfortunately, Adams is also known for, as everyone describes in the musical, as being, “obnoxious and disliked”. Many Congress members don’t listen to him or agree with him simply because of these qualities. But, it is soon discovered he does have a soft side when talking with his wife, Abigail, or meeting with Martha Jefferson. Both women are able to bring out a much more youthful, relaxed John Adams. Furthermore, Adam’s feelings for independence is expressed when he is alone and vulnerable displaying his passion and fire for the cause of freedom. Despite any flaws, he is a three dimensional character where he has a strong, magnetic quality that commands respect from others including Congress.

Age: 41

Vocal Range: C3 to Gb4 (Baritone)

Dance: Basic ballroom dancer

Benjamin Franklin – A Pennsylvania delegate. A man of many talents, Franklin is an experienced statesman, diplomat, inventor, writer, and philosopher. The oldest member in Congress and John Adams’ confidant and “partner in crime” helpnig lead the charge for independence. Despite being an older man suffering from gout and often slumbers in the most inconvenient times, he often acts younger, more youthful and energetic than everybody around him. Franklin is known for being coolheaded, courteous, logical, and very witty which makes him liked and respected by all the Congress members. He is often the one who says a funny quip to relieve any tension keeping the atmosphere from getting too serious. And, he is the one to remind Adams to think before speaking and to have a bit of fun. However, he does have his moments when he looses his patience and expresses anger when he’s had enough. When does get serious, everyone listens. His logic prevails over others’ emotions.

Age: 70

Vocal Range: G#2 to Eb4 (Baritone-Bass)

Dance: Basic ballroom dancer

Thomas Jefferson – A Virginia delegate. A very tall man. Becomes a man of many roles including an architect, a writer, a farmer, a scientist, a statesman, a lawyer, a violin player, and most importantly, the man who wrote the Declaration of Independence. At first, Jefferson was only entrusted to keep record with the daily weather report. He was known for being a man with few words. The silent, strong type of man who only speaks when necessary. Despite being a member of Congress, he only wishes to return home to his wife, Martha. But, being known as an incredible and eloquent writer, he gets roped into writing the Declaration of Independence despite his many protests. Although he is put in a position he wishes he was not placed upon, he is shown to be commanding, humorous, and downright passionate when he is called for it. He is more than what meets the eye.

Age: 33

Vocal Range: C3 to G4 (Tenor)

Dance: Mover

Supporting Characters

Other Congress Members

John Dickinson – A Pennsylvania delegate. A lawyer and a statesman. He is a leading figure who opposes independence and wishes not to break from Great Britain. An eloquent speaker and a passionate manipulator who believes he is in the right. However, when he looses the debate against independence, he choose to leave and join the army to fight for America despite his grievances.

Age: 44

Vocal Range: A2 to E4 (Baritone)

Dance: Mover

Edward Rutledge – A North Carolina delegate. A statesman and a lawyer. Despite being the youngest man in Congress, Rutledge was no pushover. He was also a leading figure who wished not to break from Great Britain, but more than that, he was a leading proponent for individual rights for each individual state. Becoming the domineering figure for both North and South Carolina, Rutledge was not happy for the abolishment of slavery in the Declaration. He threatened to vote against independence if it did not get removed. Because of his strong opposition, Jefferson agrees to remove it, and he allows North and South Carolina to vote for the Declaration.

Age: 26

Vocal Range: C3 to A4 (Baritone)

Dance: Mover

Richard Henry Lee – A Virginia delegate. Becomes the Govener of Virginia. A brash, flamboyant, and bold character who is very proud of being a member of the famous and well-respected Lee family from Virginia. Despite being a bit too loud of a character, the Congress members like him, and it’s with that fact in mind that Franklin is able to convince Lee to make an argument for independence as he and Adams are having very little luck bringing this topic to Congress and taking it seriously.

Age: 45

Vocal Range: C3 to G4 (Baritone)

Dance: Mover

John Hancock – President of Continental Congress. A merchant from Massachusetts. Because he is the mediator, Hancock must be fair during the debates, but he supports independence just as strongly as John Adams which causes him to be quite impatience with his fellow congressmen at times. So much so, that he is the first who writes his name down big and bold on the Declaration of Independence.

Age: 39

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

James Wilson – A Pennsylvania delegate. An associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Wilson is one of the quietest characters, but not by choice really, but because of his fellow delegate John Dickinson who is always talking for him. Wilson becomes a mere shadow behind Dickinson, seemingly being a “sidekick” for the lawyer. He is made fun of a lot for this position behind Dickinson. However, when push comes to shove and when he is questioned about American independence, Wilson stands up for himself, but not becomes of his own belief in the cause. Unlike the rest of the Congress members, he does not want to be remembered in history and especially not remembered as the man who opposed the rest of Congress and prevented America’s freedom from Great Britian. This causes Dickinson to reflect and ends up leaving Congress to fight for America.

Age: 34

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

Charles Thomson – The Congressional clerk and secretary. Took care of all the administrative duties, takes account of each vote, guides the topics and debates within the Congress, and reads all the letters that arrives from George Washington. He is a quiet presence in the roomand shows no favor between the north or south, but he does so much behind the scenes. Soon, Thomson evens designs the back of the Great seal of the United States.

Age: 47

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

Roger Sherman – A Connecticut delegate. Sherman was known for being on the side of independence and was put on the committee to write the Declaration. However, he was not confident in his writing abilities, did not like to be involved in any controversies, and deemed himself a simple man who couldn’t participate in the writing of the Declaration.

Age: 55

Vocal Range: C3 to A#4 (Tenor)

Dance: Mover

Robert Livingston – A New York delegate. Livingston was in favor of independence and became a part of the committee to write the Declaration. However, he was not able to help with the writing as he found out he gained a son. So, he left and traveled back home to celebrate the birth of his son.

Age: 30

Vocal Range: A#2 to F4 (Baritone)

Dance: Mover

Stephen Hopkins – The Rhode Island delegate. The second oldest member in Congress who loves rum. He is a crude, odd, crusty old man, but he is a supporter of independence.

Age: 70

Vocal Range: C3 to Eb4 (Baritone)

Dance: None

Caesar Rodney – A Delaware delegate. A older member of Congress who works incredibly hard for independence despite Delawares torn ideals. Unfortunately, he collapses during a heated debate as he is suffering from skin cancer hidden under a chin strap. He goes home to rest but decides to travel when he hears he is needed for the final vote for independence.

Age: 48

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

Thomas McKean – A Delaware delegate. A Colonel who is very tall, Scottish, argumentative, and very loud. However, he supports independence and shows compassion towards those he cares about like Caesar Rodney.

Age: 42

Vocal Range: C3 to Eb4 (Baritone)

Dance: None

Lymon Hall – The Georgia delegate. A physician and pastor. He comes in the middle during the debate for independence, and though many ask him his stance on the issue, Hall chooses to remain neutral until he makes up his mind. After a heated debate between Adams and Dickinson and Rutledge, he seems to have chosen Dickinson and Rutledge’s side. However, after he listens to Adams innermost thoughts on America’s future, he makes up his mind and choose independence.

Age: 52

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

John Witherspoon – A New Jersey delegate. A congressional Chaplain. He as well as the other delegates from New Jersey arrive in the middle during the debate for independence. Witherspoon argues for it but is very vocal for the inclusion to add God, the Supreme Being, into the Declaration which is easily accepted.

Age: 56

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

Samuel Chase – A Maryland delegate. A fat man who is always eating. At first, he sides with voting against independence as he is fearful of the consequences if they fail to win the war againt Great Britian. But after a trip to Maryland with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, he is for independence.

Age: 35

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

Lewis Morris – A New York delegate. The leader of the delegates from New York who always abstains from every vote.

Age: 50

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

George Read – A Delaware delegate. Opposes to independence despite his fellow members for it. They constantly argue over their ideals and is described as a weasel.

Age: 43

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

Joesph Hewes – A North Carolina delegate. He is a shadow behind Edward Rutledge and just supports whatever Rutledge says. However, he is against independence and sides with Rutledge on the slavery issue demanding the Declaration removes the abolishment of slavery.

Age: 46

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

Josiah Bartlett – A New Hampshire delegate. A doctor who sides in favor of independence.

Age: 46

Vocal Range: None

Dance: Mover

The Women

Abigail Adams – Wife of John Adams. Her motherly nature brings out the soft side of Adams’, but she is also quickly shown to be a woman of strong personality that rivals Adams’. Equally, she has a forceful personality and is an incredible smart woman with subtle humor. She communicates solely through letters that are filled with intellectual discussion on economics, government, and politics. Of course, not only that, but she updates John on their children and home life on the farm. Because of her mature and calm persona, she is able to give encouragement and support to John when he needs it most giving him hope when there seems to be none.

Age: 32

Vocal Range: C#4 to F5 (Soprano)

Dance: None

Martha Jefferson – Wife of Thomas Jefferson. A bright and sweet young woman who turns heads because of her beauty, Martha comes to Philadelphia at the request of John to help with Thomas’ writer’s block. Despite knowing her charm, she is thoroughly devoted to Thomas, but that doesn’t mean she can’t have fun dancing, singing, and playing instruments with others.

Age: 27

Vocal Range: A#3 to D5 (Mezzo-Soprano)

Dance: Ballroom dancer

Minor Characters

Other

Andrew McNair – The congressional custodian. McNair with his quirky personality cleans and takes care of Independence Hall such as lighting fires and candles, opening and closing windows, fetching water or rum for the congressmen, filling ink wells, and just keeping the place clean in general.

Age: 50

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

The Courier – A messenger. A young boy who has seen and knows too much of war despite his innocent appearance. He is in and out of the Independence Hall constantly delivering messages from George Washington.

Age: 15 to 20

Vocal Range: C3 to Db4

Dance: None

The Apprentice (The Leather Apron) – McNair’s assistant. A teenager in training helping McNair in his duties and learning his trade always wearing a leather apron. However, he deserves to join the Continental Army one day.

Age: 16

Vocal Range: None

Dance: None

Chorus

Continental Congressmen

A Painter

Exploring the Music, Lyrics, and Dance of “1776 the Musical”

Musical Style: Classical

Dance Requirements: Low

Vocal Demands: High

Orchestra Size: Large

Chorus Size: Large

Historical Context

Composer/Lyricist Sherman Edwards

Born in New York City in 1919, Sherman Edwards was a true renaissance man who loved history and enjoyed creating music. He gained a history degree at both New York Univeristy and Cornell before joining the Air Force in World War II. However, he quickly was placed in the public school system to teach high school history instead of being at the front lines. While he was teaching Edwards also pursued a career of music on the side as well as acting from time to time. He became a jazz pianist for Louis Armstrong, wrote pop and rock songs for celebrities like Elvis Presley, and performed in some Broadway shows.

Life was working well for him when he decided to drop the pen and stop writing rock music. For some time, he had an idea to create a musical dealing with the events leading up to the Declaration of Independence. He loved history, and he loved music, Edwards could not shake the dream of creating a story combining the two.

So, when the man turned 40, he left his jobs, pursued his passion project full time. First thing he did was create the songs and music which came to him easily. However, looking for writers to tell the story became the problem. Edwards only wanted to create the songs for the show while finding a playwright to flesh out the story and characters for him. But his quest was continually rejected. Every writer rejected his idea thinking it was boring, preachy, or utterly absurd.

Edwards ended up writing the original book for the show himself after doing years of historical research from places like Pennsylvania Historical Societies’ libraries, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Book Division of the New York Pubic Library, and his own personal archives that he possessed from his history degree. After doing the research, writing the book, and finishing the songs, he went out to pitch his new musical “1776” to producers hoping his story would take to the stage soon.

Producer Stuart Ostrow

For two years, Edwards faced rejection after rejection. Door slam after door slam. Kicked out of audition rooms with producers telling him how dumb his story was. In addition to the old arguments he was heard for years at this point, people told him the play had no modern relevance to today’s struggles. The Vietnam War was happening, students were protesting,the women’s and civil rights’ movement was underway, and there was a heavy climate of political tension and distrust. To many’s eyes, patriotism was an idea of the past. No way could a story that celebrates the birth of a new nation filled with patriotism and independence succeed.

However, when Stuart Ostrow heard Edwards’ story, the producer saw the vision. He believed the spirit of the play would resonance with audiences across America. Ostrow looked passed the big wigs saw the themes of rebellion, challenging authority, and freedom that he very much saw in the people of today. He agreed to produce the show, but he did see a problem.

Edwards’ bio wasn’t very appealing as he was an ex-history teacher with few artistic credits under his belt. If they were to create a brand new musical, he believed they needed to add someone else to the creative team with a more decorated background. Furthermore, Ostraw believed Edwards’ book needed polishing.

Writer Peter Stone

Peter Stone grew up in a household of screenwriters, and soon became a pretty famous one himself. He earned his bachelors of art degree at Bard College and got his masters in Yale University. After his studies, he started writing for television and eventually won an Emmy award for the TV show “The Defenders”. Then, he transitioned to film making his writing debut for the hit film “Charade” in 1963. Stone became a contracted studio screenwriter and even won the 1965 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for the film “Father Goose”. Afterwards, he started writing for musicals as well.

Previously, Stone was approached by Edwards to collaborate on “1776”, but he passed on the offer like so many others. However, a few years later, Ostrow approaches him and had him sit down and listen to Edwards’ songs. Once he heard “Sit Down John”, Stone was inspired and accepted the job.

The minute you heard [“Sit Down, John”], you knew what the whole show was. … You knew immediately that John Adams and the others were not going to be treated as gods or cardboard characters, chopping down cherry trees and flying kites with strings and keys on them. It had this very affectionate familiarity; it wasn’t reverential.

However, it was a challenge to write a historically-based work especially one where it involves the events of the Declaration of Independence. Stone enjoyed they process especially since majority of the work was already done by Edwards’ years of research. Still, Stone had to make sure he was creating a historically acceptable, interesting, truthful, and dramatically satisfying production. Of course, both writers had to take some liberties in order to make this happen, but they made it theri mission to stick with what was historically accurate as possible.

“1776 the Musical” Premiere

After much discourse, conflicts, and disagreements, Edwards’ vision finally saw the stage on March 16, 1969 at Broadway’s 46th Street Theatre. It won many awards including New York Drama Critics Circle for Best Musical and Tony Award for Best Music and Lyrics. It played for three years with 1,217 performances. Obviously, men in big wigs were still relevant to the modern day American people.

Fun Fact

In the 1969 original run, there was no intermission.

Act I

| Musical Number | Characters |

| Sit Down, John | John Adams and Congressmen |

| Piddle, Twiddle, and Resolve | John Adams |

| Till Then | John Adams and Abigail Adams |

| The Lees of Old Virginia | Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams |

| But, Mr. Adams | John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston |

| Yours, Yours, Yours | John Adams and Abigail Adams |

| He Plays the Violin | Martha Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams |

| Cool, Cool, Considerate Men | John Dickinson, Edward Rutledge, and Congressmen |

| Momma Look Sharp | The Courier, Andrew McNair, and The Apprentice (The Leather Apron) |

Act II

| Musical Number | Characters |

| The Egg | Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Congressmen |

| Molasses to Rum | Edward Rutledge |

| Compliments | Abigail Adams |

| Is Anybody There? | John Adams and Charles Thomson |

Fun Fact

In the 2022 revival, the end of Act I is moved to after “He Plays the Violin”.

Reality Vs. Fictional: “1776 the Musical” Historical Inaccuracies

In the book of “1776 the Musical”, it includes a section called “Historical Note by the Authors” that brings to light all the differences from their story versus what happened in real life.

The first question we are asked by those who have seen—or read—1776 is invariably: “Is it true? Did it really happen that way?” The answer is: Yes. Certainly a few changes have been made in order to fulfill basic dramatic tenets … reality is seldom artistic, orderly, or dramatically satisfying; life rarely provides a sound second act, and its climaxes usually have not been adequately prepared for. Therefore, in historical drama, a number of small licenses are almost always taken with strictest fact, and those in 1776 are enumerated in this addendum. But none of them, either separately or in accumulation, has done anything to alter the historical truth of the characters, the times, or the events of American independence.

Please note:

The play’s narrative is crafted from later accounts and educated guesses, as Congress met in secrecy and no contemporary records of the debate over the Declaration of Independence exist. The authors invented scenes and dialogue to enhance storytelling, sometimes using words written by the historical figures years or even decades after the events, and rearranged them for dramatic impact.

Things Altered

Declaration, though reported back to Congress for amendments and revisions prior to the vote on independence on July 2, was not actually debated and approved until after that vote. However, had this schedule been preserved in the play, the audience’s interest in the debate would already have been spent.

Many historians debate about when the Declaration of Independence was officially signed as there are records of many Congressmen not present during the months of June and July. Some argue it was July 2nd, others July 4th, and many believe it was August 2nd. So, instead of dragging out the debates and signings to August, Edwards and Stone believed combining signings to one day is much more efficient. So the play quickly transitions from debating the idea of freedom to debating the document to signing the document in a much more quick manner.

Other

Many characters in “1776” differ from their historical counterparts, particularly in the portrayal of John Adams as “obnoxious and disliked”. However, historians notes that Adams was actually one of the most respected members of Congress in 1776. Adams’ own description of himself as “obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular” comes from a letter written in 1822, 46 years later, likely influenced by his experiences during his unpopular presidency. It is factual that no delegate described Adams as obnoxious in 1776.

John Adams is a composite character, blending the real John Adams with his cousin Samuel Adams, who was also a member of Congress at the time but is not depicted in the play, though he is mentioned.

While the musical portrays Caesar Rodney as an elderly man nearing death from skin cancer, he was actually only 47 at the time and remained very active in the Revolution after signing the Declaration. His absence from the vote was not due to health reasons. However, the play accurately depicts his dramatic arrival after riding 80 miles the night before.

In the musical and film, John Adams is depicted as disliking Richard Henry Lee. However, according to historians, Adams actually respected and admired Lee. The portrayal of Adams disliking Franklin is more accurate, as Adams did indeed have a strained relationship with him.

James Wilson is portrayed as a follower of Dickinson who only changes his vote so he would not remembered. This is completely untrue as Wilson was considered of the leading thinkers behind the American Revolution. He was always arguing for independence and consistently supported those were on his side. However, it is true he would not cast a vote until his fellow delegates made an agreement together.

The portrayal of James Wilson as an indecisive, cowardly man in the play is inaccurate. The real Wilson, who was not a judge in 1776, had been cautious about supporting independence initially, but he voted in favor of the resolution when it came up. In reality, Pennsylvania’s deciding swing vote was cast by John Morton, who is not depicted in the musical.

When John Adams gives the instructions to Abigail about how to make saltpeter he names various chemicals by their modern names. Instead of “sodium nitrate”, it would’ve been “soda niter”, and “potassium chloride” would’ve been “potash”. Also, you would have to use more than those two chemicals to make salpeter like manure and bat guano.

In the musical, John Adams prediction about Benjamin Franklin being a well known figure in future generations is a direct quote from Adams letter in April 1790 after Franklin’s death, but the horse was added in by the writers:

Franklin smote the ground and out sprang George Washington. Fully grown, and on his horse. Franklin then electrified them with his magnificent lightning rod and the three of them Franklin, Washington, and the horse conducted the entire Revolution all by themselves.

The quote by Edmund Burke that Dr. Lyman Hall quoted to John Adams is actually a paraphrase of a real statement by Burke:

Your Representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.

Things Surmised

The final logical conjecture we made concerned the discrepancy between the appearance of the word ‘inalienable’ in Jefferson’s version of the Declaration and its reappearance as ‘unalienable’ in the printed copy that is now in universal use. This could have been a misprint, but it might, too, have been the result of interference by Adams… There is no doubt that the meddlesome ‘Massachusettensian,’ a Harvard graduate, was not above speaking to Mr. Dunlap, the printer.

It is true that the only difference when the Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence and the copies made by the printer is the change from the word “inalienable” to “unalienable”. Many speculated whether this was a faulty mistake on the printer’s John Dunlap’s fault, or if John Adams had something to do with it. Adams did have a copy of the declaration with the spelling “unalienable”, and he is believed to have been one of the men who supervised Dunlap’s first printing. He was a man who was very stubborn particularly on writing so he might of inserted his preferred spelling, but both spellings are correct so it doesn’t really matter.

It is unknown… whether Richard Henry Lee was persuaded to go to the Virginia House of Burgesses in order to secure a motion of independence that could be introduced in Congress, or if he volunteered on his own. Certainly Adams was getting nowhere with his own efforts…

It is true that John Adams and Richard Henry Lee were the most vocal supporters for independence, and it is true when Lee brought his resolution to Congress, it was seconded by Adams. However, the scene were Adams and Franklin convince and send Lee to Virginia is false. Lee never went to Virginia at all. At least, there is no record or accounts of being going to the state in May 1776. His resolution was sent to him from the Virginia House of Burgesses. However, Edwards and Stone weren’t sure if Lee traveled at the time so they made up their own version with a fabulous song.

Things Added

The tally board used throughout the play to record each vote did not exist in the actual chamber in Philadelphia. It has been included in order to clarify the positions of the thirteen colonies at any given moment, a device allowing the audience to follow the parliamentary action without confusion.

Stone added in a tally board as well as a calendar into the script to help show the viewers the passage of time more clearly.

Adams, Franklin, and Chase are shown leaving for New Brunswick, New Jersey, for an inspection of the military. This particular trip did not actually take place, though a similar one was made to New York after the vote on independence, during which Adams and Franklin had to share a single bed in an inn.

The trip John Adams and Benjamin Franklin convince Samuel Chase to go with them on in the script did not happen. However, this piece of the script was inspired by a similar trip made by Adams, Franklin, and Edward Rutledge in September 1776.

While it is true that Jefferson missed [Martha] to distraction, more than enough to effect an unscheduled reunion, it is believed that he journeyed to Virginia to see her. The license of having her come to see him, at Adams’ instigation, stemmed from our desire to show something of the young Jefferson’s personal life without destroying the unity of setting.

Martha Jefferson’s addition into the musical is completely fictional. For one, Thomas and Martha were not newlyweds, but in actuality, the Jeffersons had been married for four years. Secondly, while Thomas did long for his wife, it was not because of lust. In 1776, Martha had a miscarriage and was very ill, and Thomas was worried for her. Obviously, the third point is Martha was in one condition to travel to Philadelphia so she never visited her husband. In his writings, it is obvious Martha’s health was taking a toll on his mental and emotional wellbeing in 1776, and he even begged Richard Henry Lee to let him go back home.

Other

In the musical, Richard Henry Lee states that he is returning to Virginia to serve as governor. However, he never held that position. It was his cousin, Henry Lee III who eventually became governor and was also the father of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

In the musical, Edward Rutledge led the opposition to the anti-slavery clause, but this is incorrect. His leadership is completely fictional. The only factual information about this circumstance is from Jefferson stating that the clause was opposed by South Carolina, Georgia, and a few other individuals from the north.

After a debate over slavery whether the clause about slave trade should be added or not, in the musical, all of the southern delegates walk out in protest making it clear they will only support independence when the clause is removed from the Declaration. A walkout never actually happened and is purely fictional, and also, most of the delegates in the north and south supported the clause being removed.

In the musical, Thomas Jefferson states he has resolved to free his slaves, but this is completely false. While he was alive, Jefferson never freed any of his slaves. It wasn’t until after his death, that only a few of them were freed.

Benjamin Franklin claims to be the founder of an abolitionist organization, but in real life, he was not an active abolitionist until after the American Revolution. He became president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1785.

In the 2022 revival production, the story included an excerpt from Abigail Adam’s letter known as “Remember the Ladies”.

The myth that the Liberty Bell rang as the delegates were signing the Declaration on July 4th is just that a myth. The Liberty Bell did not ring and was actually lowered in the upper chamber of Independence Hall. Some historians believe that a smaller bell could have been run on July 8 when the Declaration was read to the public.

Things Deleted

There is, after all, a limit to an audience’s ability to assimilate (and keep separate) a large number of characters, as well as the physical limits of any given stage production. For this reason several of the lesser known (and least contributory) Congressmen were eliminated altogether, and in a few cases two or more were combined into a single character. James Wilson, for example, contains a few of the qualities of his fellow Pennsylvanian, John Morton. And John Adams is, at times, a composite of himself and his cousin Sam Adams.

Because there were 56 Congressmen, Edwards and Stone had to take out quite a few characters in order to tell a 3 hour story. As a result, many of the delegations had only one or two men from each state. The only delegation that was correct was Delaware. With these changes, the actual voting was oversimplifiy to help the story as well as help the audience keep track of the voting.

Other

The musical notably highlights Martha Jefferson and Abigail Adams but does not include Mary Norris, the wife of Dickinson, who was actually in Philadelphia at the time and had a unique perspective compared to the other wives. Franklin’s common-law wife, Deborah Read, had already passed away by this time, and his mistresses are not portrayed, though he does reference a ‘Rendez-vous’ he needs to attend.

The terms “right” and “left” in politics did not exist during the events of the Declaration of Independence. They were first recorded to be used during the French Revolution in 1789.

The story omits the views of the Quakers in which John Dickinson was one. Although he was a loyalist and respected Great Britian, he also had issues and objections on the tax laws made by the King George III. He was no more wealthier than other Congressmen and even freed his slaves in 1777. Furthermore, as a Quaker, he did not agree with violence and would do everything possibe to avoid such aggressive actions. Dickinson would never fight Adams and especially not insult Adams as a lawyer when he was one as well.

Dickinson’s background which greatly influenced his stance in Congree was not show in the musical. He refused to sign Adams’ and Jefferson’s declaration, which was based on the ‘rights of man’ and ‘natural law,’ as he aimed to avoid reopening contentious issues from the English Civil Wars, including Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan regime and the Jacobite cause. These issues had been settled in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, leading to the constitutionalization of the English Bill of Rights, which emphasized the ‘rights and responsibilities of person’ rather than the ‘rights of man,’ a term only used in the context of treason. The last Jacobite rebellion, which sought to restore Catholicism and the religious concept of ‘natural law,’ had occurred as recently as 1745.

“1776 the Musical” Fun Facts

Caesar Rodney of Delaware, suffering from skin cancer, never appeared in public without a green scarf wrapped around his face.

Rodney did have skin cancer on his face and always wore a scarf to cover it. However, no one is positively sure it was a green scarf.

Ben Franklin’s illegitimate son William was Royal Governor of New Jersey until he was arrested, in June 1776, and exiled to Connecticut.

William Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s only son who survived to adulthood, was a Loyalist which greatly strained his relationship with his father. He was appointed as the Royal Governor of New Jersey before he was arrested a few years later deemed an enemy of the United States. Benjamin Franklin disowned his son, but he remained close with William’s son, Temple Franklin, who became his secretary.

Rhode Island’s Stephen Hopkins, known to his colleagues as ‘Old Grape and Guts’ because of his fondness for distilled refreshment, always wore his round black, wide-brimmed Quaker’s hat in the chamber.

Hopkins was an odd man in Congress who always drank from morning to evening, but he wasn’t classified as a dunkard as he never drank to stupidity and was regarded as someone very smart.

None of the five members of this committee wanted the assignment of actually writing the Declaration, and all of them begged off for one personal reason or another.

It is true that John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were the five members of the writing committee. However, all of them had reasons for writing the Declaration of Independence. There is also no evidence that Sherman or Livingston were considered being principal writers for the declaration. Furthermore, Livingston was leaving for New York, but not for the birth of a new son, but for the New York Convention at that time.

None of the five members of this committee wanted the assignment of actually writing the Declaration, and all of them begged off for one personal reason or another.

It is true that John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were the five members of the writing committee. However, all of them had reasons for writing the Declaration of Independence. There is also no evidence that Sherman or Livingston were considered being principal writers for the declaration. Furthermore, Livingston was leaving for New York, but not for the birth of a new son, but for the New York Convention at that time.

Jefferson was, besides being an author, lawyer, farmer, architect, and statesman, a fine violinist.

It is fact that at a young age Jefferson learned to play the violin, and many believe he used this talent to gain the attention of Martha. She was very fond of music and also sang and played the harpsichord.

Debate over the Declaration included the deletion of “a strong condemnation of that ‘peculiar institution’ slavery (accusing King George III of waging ‘cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere…”) which called for its abolition. This paragraph was removed to placate and appease the Southern colonies and to hold them in the Union.

Thomas Jefferson’s “Notes of Proceedings in the Continental Congress” explains that, “the clause… reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina & Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our Northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.” Edwards puts these words into Edward Rutledge’s mouth in the song “Molasses to Rum”.

The New York delegation abstained on many votes, including the final vote on independence.

It is fact that New York abstained from all votes including the vote for independence and the vote for the Declaration of Independence.

The deadlock existing within the Delaware delegation of the mortally ill Caesar Rodney, who, in great pain, had ridden all night from Dover, a distance of some eighty miles, arriving just in time to save the motion on independence from being defeated.

Rodney did ride through the night to arrive in Philadephlia for the final note, but Thomas McKean did not travel to Delaware to help Rodney.

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, the leader of the anti-independence forces (desiring reconciliation with England), refused to sign the Declaration, a document he felt he could not endorse. But, asserting a fidelity to America, he left the Congress to enlist in the Continental Army as a private—though he was entitled to a commission—and served courageously with the Delaware Militia. Some years later he was appointed to the Constitutional Convention, representing Delaware, and returned to Philadelphia to contribute greatly to the writing of that extraordinary document, the United States Constitution.

It is true that Dickinson did refuse to sign the Declaration. However, he was absent when the vote commenced as he went to serve as Brigadier General in Pennsylvania Associators.

Other

Abigail’s request for pins was not frivolous request. The pin was a tool to use for replacing, rusting, and breakage. Women used them for a variety of things like crafts, garments, headgear, making lace, and textiles.

Dialogue Similarties

How does the dialogue in “1776” compare to the real life speeches and writings of these characters?

| Dialogue from the Musical | Writings from Speeches and Letters |

| John Hancock, Scene 1: “I now call the Congress’ attention to the petition of Mr. Melchior Meng, who claims twenty dollars’ compensation for his dead mule. It seems the animal was employed transporting luggage in the service of the Congress.” | Journals of the Continental Congress, June 6, 1776: “The Committee of Claims reported, that there is due, … To Melchior Meng, for twenty one days hire of this waggon and horses, carrying money to Virginia, the sum of £15.” |

| Abigail and John Adams, “Yours, Yours, Yours”: “I am, as I ever was, and ever shall be, Yours… Yours… Yours…” | John Adams, Letter to Abigail Adams, February 16, 1780: “I am as I ever was and ever shall be Yours, Yours, Yours” |

| Abigail Adams, “Yours, Yours, Yours”: “I live like a nun in a cloister, / Solitary, celibate, I hate it.” | Abigail Adams, Letter to John Adams, November 12, 1775: “I have been like a nun in a cloister ever since you went away, have not been into any other house than my Fathers and Sisters, except once to Coll. Quincys.” |

| John Adams, Scene 4: “It doesn’t matter. I won’t appear in the history books, anyway only you. Franklin did this, Franklin did that, Franklin did some other damned thing. Franklin smote the ground, and out sprang George Washington, fully grown and on his horse. Franklin then electrified him with his miraculous lightning rod, and the three of them—Franklin, Washington, and the horse—conducted the entire Revolution all by themselves.” | John Adams, Letter to Benjamin Franklin, April 4, 1790: “The History of our Revolution will be one continued Lye from one End to the other. The Essence of the whole will be that Dr Franklins electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod—and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War.” |

| George Washington (Dispatch read by Charles Thomson), Scene 5: “Oh, how I wish I had never seen the Continental Army. I would have done better to retire to the back country and live in a wigwam.” | George Washington, Letter to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, January 14, 1776: “I have often thought how much happier I should have been, if, instead of accepting of a command under such Circumstances I had taken my Musket upon my Shoulder & enterd the Ranks, or, if I could have justified the Measure to Posterity, & my own Conscience, had retir’d to the back Country, & lived in a Wig-wam…” |

| Edward Rutledge, Scene 7: “Then what’s that I smell floatin’ down from the North—could it be the aroma of hy-pocrisy? For who holds the other end of that filthy purse-string, Mr. Adams? Our northern brethren are feelin’ a bit tender toward our slaves. They don’t keep slaves, no-o, but they’re willin’ to be considerable carriers of slaves—to others! They are willin’, for the shillin’…” | Thomas Jefferson, Notes of Proceedings in the Continental Congress: “Our Northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.” |

| John Adams, “Is Anybody There?”: “I see / Fireworks! / I see the Pageant and Pomp and Parade! / I hear the bells ringing out / I hear the cannons’ roar!” | John Adams, Letter to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776: “It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” |

| John Adams, “Is Anybody There?”: “Through all the gloom, / Through all the gloom, I can / See the rays of ravishing light and / Glory!” | John Adams, Letter to Abigail Adams, July 1776: “Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory.” |

| John Adams: “Good God!” | John Adams, Draft of an essay, January 1761: “Good God! where are the Rights of English Men! where is the spirit, that once exalted the souls of Britons and emboldened their [faces] to look even Princes and Monarchs in the face.” John Adams, Letter to Charles Lee, October 13, 1775: “Good God! What shall We say of human Nature? What shall We say of American Patriots? or rather what will the World Say?” John Adams, Letter to Abigail Adams, September 26, 1802: “Good God! Is this a public Man sitting in Judgment on Nations? And has the American People so little Judgment, Taste and Sense to endure it?” John Adams, Letter to Thomas Jefferson, May 1, 1812: “Good God! Is a President of the U.S to be Subject to a private Action of every Individual? This will Soon introduce the Axiom that a President can do no wrong; or another equally curious that a President can do no right.” |

Broadway Buzz: 1776

“On the face of it, few historical incidents seem more unlikely to spawn a Broadway musical than that solemn moment in the history of mankind, the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Yet, 1776, which opened last night at the 46th Street Theater, most handsomely demonstrated that people who merely go on the face of it are occasionally outrageously wrong. Come to think of it, that was also what the Declaration of Independence demonstrated, so there is a ready precedent at hand. 1776, which I saw at one of its critics’ previews on Saturday afternoon, is a most striking, most gripping musical. I recommend it without reservation. It makes even an Englishman’s heart beat a little bit faster. This is a musical with style, humanity, wit and passion. The credit for the idea of the musical belongs to Sherman Edwards, who has also contributed the music and lyrics. The book is by Peter Stone, best known as a Hollywood screenwriter. The two of them have done a fine job. The authors have really captured the Spirit of ’76. The characterizations are most unusually full for a musical, and even though the outcome is never in any very serious doubt, 1776 is consistently exciting and entertaining, for Mr. Stone’s book is literate, urbane and, on occasion, very amusing. The music is absolutely modern in its sound, and it is apt, convincing and enjoyable.”

– Clive Barnes, The New York Times, March 17, 1969

“A magnificently staged and stunningly original musical was presented last evening at the 46th St. Theater. It is far, far off the Broadway path and far away in time. Its simple title is 1776 and its story concerns the writing of our Declaration of Independence. This is by no means a historical tract or a sermon on the birth of this nation. It is warm with life of its own; it is funny, it is moving. It plays without intermission, because an intermission would break its spell. It is an artistic creation such as we do not often find in our theater. Often, as I sat enchanted in my seat, it reminded me of Gilbert and Sullivan in its amused regard of human frailties; again, in its music, it struck me as a new opera. And the men who, after months of debate-some of it silly and petty-finally put their John Hancocks on our Document became miraculously human. The author of music and lyrics is Sherman Edwards, a onetime history professor who became a popular song writer. Edwards has worked on his conception for a decade, and now Peter Stone, known mostly as a scenarist, has made this idea into a libretto which works perfectly on a musical stage.”

– John Chapman, Daily News, March 17, 1969

“The United States has become the well-spring of successful musical comedies of the English-speaking world in the past quarter century, but no one had written about that most American of events, the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This omission has now been corrected with the appearance at the Forty-Sixth Street Theater of 1776 (that’s all there is to the title), presented by Stuart Ostrow with music and lyrics by Sherman Edwards and book by Peter Stone. We now really have our own thing in a musical, and it is pleasant to report that it is first-rate both as musical entertainment and as a semi-documentary. It is absorbing and exciting, and if history has been manipulated a bit here and there for dramatic purposes, the character of the men and the events of those remarkable months in Philadelphia come through admirably.”

– Richard P. Cooke, The Wall Street Journal, March 18, 1969

“In this cynical age, it required courage as well as enterprise to do a musical play that simply deals with the events leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence. And 1776, which opened last night at the 46th St. Theater, makes no attempt to be satirical or wander off into modern by-paths. But the rewards of the confidence reposed in the bold conception were abundant. The result is a brilliant and remarkably moving work of theatrical art. 1776 has no plot in a conventional sense, and it makes no attempt to romanticize the Founding Fathers. It shows the delegates to the Continental Congress who met in Philadelphia that hot summer as a group of highly fallible, quarrelsome and sometimes pig-headed men, who dawdled away their days in bickerings and doubts, much to the indignation of John Adams, who wanted to get ahead with the business in hand. Yet they did somehow arise to the greatness of the momentous occasion. The attractive song numbers by Sherman Edwards are imaginatively brought in, Peter Stone’s book is always skillful, and it handles the lighter moments, such as the brief romantic interludes for Jefferson and Adams, with sense and deftness. 1776 is a most exhilarating accomplishment.”

– Richard Watts, New York Post, March 17, 1969

Awards Won

Tony Award

1969 – Supporting Actress In A Musical Play, Nominee (Virginia Vestoff)

1969 – Best Performance By A Featured Actor In A Musical, Winner (Ronald Holgate)

1969 – Best Performance By A Featured Actress In A Musical, Nominee (Virginia Vestoff)

1969 – Director Of A Musical Play, Winner (Peter Hunt)

1969 – Best Direction Of A Musical, Winner (Peter Hunt)

1969 – Musical Play, Winner (Peter Stone (book), Sherman Edwards (music and lyrics), Stuart Ostrow (producer)

1969 – Best Scenic Design, Nominee (Jo Mielziner)

1969 – Scenic Design, Nominee (Jo Mielziner)

1969 – Supporting Actor In A Musical Play, Winner (Ronald Holgate)

1969 – Supporting Actor In A Musical Play, Nominee (William Daniels (His name was removed from the ballot prior to voting at his request))

1998 – Best Direction Of A Musical, Nominee (Scott Ellis)

1998 – Actor In A Featured Role (Musical), Nominee (Gregg Edelman)

1998 – Director (Musical), Nominee (Scott Ellis)

1998 – Revival (Musical), Nominee (Roundabout Theatre Company, Todd Haimes, Ellen Richard, James M. Nederlander, Stewart F. Lane, Rodger Hess, Bill Haber, Robert Halmi, Jr., Dodger Endemol Theatricals, Hallmark Entertainment (producers)

1998 – Best Revival Of A Musical, Nominee (1776)

1998 – Best Featured Actor in a Musical, Nominee (Gregg Edelman)

Drama Desk Award

1969 – Outstanding Book of a Musical, Winner (Peter Stone)

1969 – Outstanding Costume Design, Winner (Patricia Zipprodt)

1998 – Best Featured Actor in a Musical, Winner (Gregg Edelman)

1998 – Outstanding Actor in a Musical, Nominee (Brent Spiner)

1998 – Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical, Winner (Gregg Edelman)

1998 – Outstanding Revival of a Musical, Nominee (1776)

NY Drama Critics Circle Award

1969 – Best Musical, Winner (1776)

Theater World Award

1969 – Theater World Award, Winner (Ken Howard)

Outer Critics Circle Award

1969 – Best Composer / Lyricist, Winner (Sherman Edwards)

Conclusion

In conclusion, “1776” is more than just a historical retelling; it is a poignant and thought-provoking portrayal of a critical moment in American history. Through its engaging characters, memorable music, and exploration of enduring themes, the musical provides both an educational and emotional experience. It reminds us that the journey to independence was fraught with challenges and that the creation of a new nation required not only bold ideas but also the willingness to face and overcome deep-seated divisions. “1776” stands as a tribute to the enduring spirit of determination and the ever-relevant quest for freedom and justice.

Sources

The following is where I got my information from:

If you would like more information on the history of the 1776, here are some resources:

“1776 the Musical” FAQ

About the Author

Kim M.

I am a 20 something year old who enjoys a peaceful life in the country while simultaneously living for the drama in the stories I find myself reading everyday. Before my life in the quiet countryside, I lived in a life full of chaos and drama in the world we called musical theatre.

No responses yet